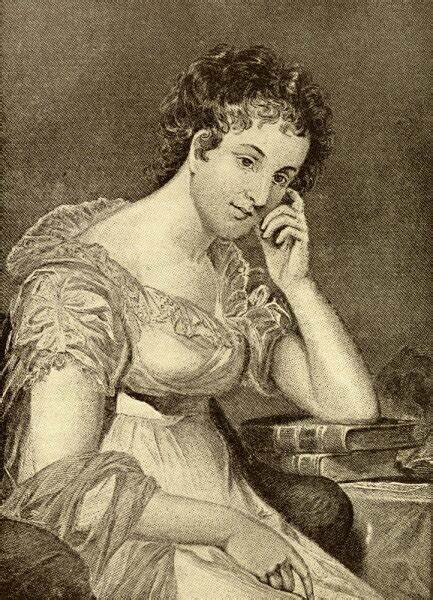

Maria Edgeworth was in the generation of authors just before Jane Austen. She was known for her bestsellers Castle Rackrent (1800) and Belinda (1801), among many other works. It is certain that Jane Austen studied her novels.

Edgeworth’s Belinda begins as elegantly as an Austen novel:

“Mrs. Stanhope, a well-bred woman, accomplished in that branch of knowledge, which is called the art of rising in the world, had, with but a small fortune, contrived to live in the highest company. She prided herself upon having established half a dozen nieces most happily; that is to say, upon having married them to men of fortunes far superior to their own.”

A new reader, presented with such a beginning, might easily conclude that this is an undiscovered Austen novel. These sentences even contain examples of the ironic interpolations that are a hallmark of Austen’s style (“which is called the art of rising in the world”; “that is to say, upon having married them to men of fortunes far superior to their own”).

But by chapter four, it is evident that Belinda must be by an author other than Jane Austen.

Edgeworth is a fine writer, and still worth reading today, but Jane Austen is among the greatest novelists in the world.

I imagine Austen reading Belinda. She sees many elements that she admires, but also opportunities for improvement.

First, Austen eliminates the chapter titles. Chapter titles are apt for fantastical works such as Alice in Wonderland or expressionist works such as Great Expectations, but chapter numbers are apt for a novel that presents itself as an objective account (War and Peace, Pride and Prejudice).

Second, she keeps Edgeworth’s parallel sentence structures and adopts her ironic interpolations.

Third, she drastically shortens the dialogues and adds subtexts to every one of them. No dialogue is included only to advance the plot.

Fourth, she shifts the narrative distance, typically pulling back at the beginning of each chapter, then drawing closer for dialogue and reactions to dialogue, then pulling back again to end the chapter, with inventive transitions between each shift.

Fifth, she rejects Edgeworth’s easy sensationalism (the drug addiction, the libelous letter, the wound on the breast). Austen is more interested in the small comedies and smaller torments of daily life.

Sixth, she resists displaying how much she knows about literature, history, and foreign languages. Edgeworth likes to show her reader that she could quote a French poet; Austen likes to show that Marianne could quote Cowper. Austen’s novels aren’t displays of erudition, but investigations into characters and incidents.

There are more differences, and many are subtle.

Art is found in the details, and Austen diligently attends to them.

But let us remember . . . Maria Edgeworth has given us the wonderful character Lady Delacour in her exuberant novel Belinda.

Orlando Bartro is the author of Toward Two Words, a comical & surreal novel about a man who finds yet another woman he never knew, usually available at Amazon for $4.91.